The Royal Gardens of Venice came into being as part of the Napoleonic program to rebuild the Piazza San Marco area. The deci- sion to use the Procuratie Nuove building to house the Royal Palace was formalized in Bonaparte’s decree of January 11, 1807.

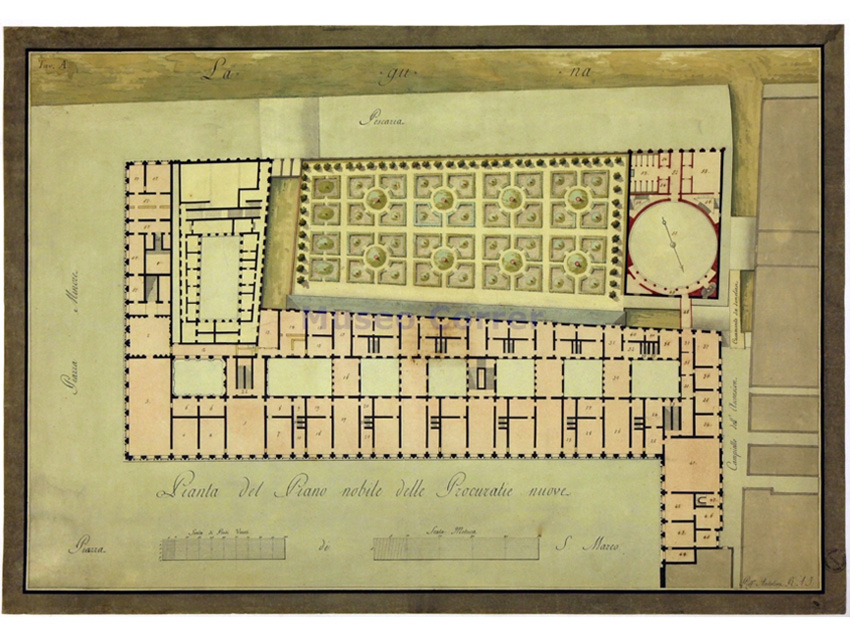

The architect Giovanni Antonio Antolini, summoned to Venice in 1806, drew up the original project for the palazzo: a new building overlooking the Bacino di San Marco (never built), and a garden in the space between the Procuratie and the lagoon, replacing the fourteenth-century Terranova granaries. Viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais modified Antolini’s plans, opting for the construction of a monumental edifice, which came to be called the Napoleonic Wing, that would occupy the area in the square where the Church of San Geminiano had stood. He instead left unchanged the plans for the gardens that made it possible to have a direct view and access to the Bacino di San Marco.

In 1810, after the granaries and workshops present on the site had been pulled down, the architect Giuseppe Maria Soli oversaw the first work: construction of a stone balustrade and of a wooden bridge that made it possible to enter the gardens from the Palazzo.

In 1814, after the Austrians’ return to the city, the architect Lorenzo Santi (1783-1839) was put in charge of building the Royal Palace. A native of Siena, Santi had studied in Rome, where he met Canova, and it was Canova who suggested in 1809 that he design the Venetian residence and oversee construction.

In 1815, with the demolition of the bridges over Rio della Luna, removing its connection to Calle Vallaresso, the garden was isolated from the city, but a drawbridge built over a small internal canal provided direct access from the Palazzo, while also allowing gondolas to pass. The entire area was enclosed with a stone balustrade and in 1816 a monumental iron gate constructed by the smiths Pietro Acerboni and Daniele Pellanda was set between the gardens and the canal bank leading to Piazzetta di San Marco.

Santi gave the garden its final form, creating a tree-lined avenue along the Bacino di San Marco, formal geometric “Italianate” parterres, and a small “English-style” wooded grove at each of its ends, whose trees, flowering plants and potted citrus trees came from the Royal Park in Stra.

Between 1815 and 1817, a greenhouse was built flanking Ponte della Zecca and, as the closing point of the perspective of the new avenue, Santi placed the Cafehaus, a neoclassical pavilion whose elaborate sculptural decorations were completed in 1819.

In the mid-nineteenth century the original geometrically designed flowerbeds were replaced by ones with more sinuous lines, in keeping with the fashion for “English-garden style” then popular in Europe. These remained substantially unchanged until the eve of the sec- ond world war. In 1857 Emperor Franz Joseph, in an attempt to win back support from the city’s populace after the harsh repressive measures that had followed the revolutions of 1848-49, allowed the public to walk along the path flanking the Bacino. This made it necessary to use long iron railings to separate the path, now open to the public, from the garden, used exclusively by the court. The gate that since 1816 had limited access to the gardens from Ponte della Zecca was moved to mark the new entry to the Gardens; its monumental character was emphasized by two new stone pillars topped by imperial eagles, subsequently removed when Venice became part of the Kingdom of Italy. It was also at this time that the iron and cast iron pergola running the length of the gardens was designed to provide a shaded private walk that could take the place of the tree-lined avenue along the Bacino. It was adapted from a temporary “covered street” constructed to welcome the monarchs in November 1856. Lorenzo Santi’s pavilion, until that time used in summer by members of the court and in winter as a greenhouse, was also opened to the public as a coffee house.

Permission for the public to use the avenue, revoked by Empress Sissi in 1861, was then reconfirmed by the Savoy monarchs in 1866 and access from Piazzetta di San Marco to the avenue was furnished by an iron bridge along the edge of the water in Rio della Zecca, opened in 1872, while the gardens and palazzo remained connected by an iron drawbridge rebuilt in 1893 and still present.

Use of the gardens changed radically after the first world war. In fact on December 23, 1920, the Royal Gardens along with other properties ceded by the Crown to the State Property Office, were entrusted to the City of Venice and opened in their entirety to the public. Although the City kept the sinuous layout of their flowerbeds, it made minor modifications in their design to facilitate the circulation of visitors. Several possible solutions for entering the gardens from Piazza San Marco via the former Royal Palace were considered and the simplest, consisting in passing through the courtyards and over the drawbridge, was the one chosen. It was adopted experimentally in 1923, but suspended by Mussolini the following year. Between 1939 and 1940 the garden’s layout once more became geometrical with ample use of dwarf box and privet, in keeping with the fascist regime’s cultural policy of affirming the superiority of the “Italian- style garden”.

Lorenzo Santi’s Pavilion, which since the late nineteenth century had ceased to be used as a Cafehaus, served for over sixty years as the Headquarters of the Bucintoro Rowing Club. In 1962 it became the Air Terminal of the new airport and finally an information point of the municipal tourist office. In recent decades, lacking necessary upkeep and maintenance, the Gardens became derelict and dilapidated. The pergola was in ruins, the drawbridge unusable, the gate rusted and crumbling, a concrete bunker constructed during the second world war occupied the central area, and service buildings put up over the years were in an advanced state of disrepair.

On December 23, 2014, the State Property Office entrusted the management of the Royal Gardens to the Venice Gardens Foundation so that it would restore them and be responsible their care and conservation in the years to come.